The Tree of Life Web Project began its journey almost 40 years ago, and was formally announced in early 1996. It has served thousands of pages of information about the evolutionary tree of life and the characteristics of organisms that evolved along its branches; this content was contributed and curated by hundreds of biologists who were experts in particular branches of life.

I no longer have the resources to keep the project functioning as it has been, and thus it will be retired soon (by the time you read this, it may have been retired). I have hopes that it will be reborn in a more primitive way as a series of static web pages that capture a snapshot of the content it contained when it ended. If so, you should eventually see, at its old web address http://tolweb.org, a basic version of the content.

Early history

The first glimmerings of the Tree of Life Web Project (ToLWeb) began sometime in the late 1980’s, when I was working on the computer program MacClade instead of working on my PhD thesis. MacClade was a phylogenetic analysis program for the Apple Macintosh that displays interactive phylogenetic trees. Inspired by Hypercard, I planned to add a feature to MacClade that would allow the taxa at the tips of the branches of the tree on the screen to be hypertext links to MacClade files that showed trees for those less-inclusive taxa. The idea was that when the user touched on, say, the terminal taxon “mammal” in a tree of vertebrates, MacClade would close down the current file, and open the mammals file, and present the user with the stored tree for mammals. This seemed like enough of a pain to implement (and really, the thesis was waiting) that the idea was shelved until sometime around 1993, when the idea resurfaced.

The connection of phylogenetic trees with hypertext links is certainly not unique to the Tree of Life Web Project, and a number of other projects have used and use similar formats. Perhaps the two most well-known examples other than ToLWeb are LifeMap, an excellent CDROM produced in 1992 by the California Academy of Sciences, and University of California at Berkeley’s Phylogeny of Life project. But there have been and now are others, and there are several websites that contain classifications connected via hypertext links.

In 1993, I did some more thinking about this. The obvious medium in which to present these linked pages was no longer MacClade, but the youthful World Wide Web. At first, the vision was to have the system just be a way to organize a bit of content and other web sites in a phylogenetic fashion. The vision grew, however, and the idea was formed of having the Tree itself distributed around the world, with different branches residing on different computers, and with a worldwide collection of experts authoring informative pages for their particular branches. I presented to my brother Wayne the idea of having a global Tree of Life on the Web. It wasn’t until the summer of 1994 that he finally convinced me this was worth doing, and we got off our rears (the theses were long finished at that point, which was a shame, as theses are very productive for the displacement activities they inspire).

This would take a long time to do if specialized tools were not available to somewhat automate the process. I suggested adding features to MacClade that would produce formatted HTML pages containing trees. Wayne took the bull by the horns and added the first versions of these tools to MacClade. The first version of the Tree, put on line in prototype form on 16 November 1994, was written entirely using this version of MacClade. Later that year I took over the development of these tools.

I sent out some notices on some relevant lists (e.g. entomo-l, TAXACOM, etc.) asking for suggestions and contributors, but we did not announce the project formally to the Internet community as a whole. Over the next few months the Tree went through some major appearance changes, in response in part to these suggestions.

Addition of remote branches and formal announcement of the Tree

In the early days, all pages on the Tree were on the home site in Tucson, Arizona. On 1 June 1995, the first remote branch of the Tree was added, the crayfish pages by Keith Crandall (U. Texas). These files resided on a computer in Austin, Texas. In the following months, a number of remote branches were added. Some of the branches of the Tree that were authored by people other than Wayne or me, and which were attached to the Tree when the Tree was first formally announced, include (among others) Peter Beerli’s Western Palearctic water frogs, Scott Stockwell’s scorpion pages, and John Lundberg’s pages on Chordata, Vertebrata, and various fishes.

On 5 January 1996, when the Tree of Life project was first formally announced, the Tree itself contained 948 pages, housed in seven computers on two continents.

Growth of the Tree, with conversion to a dynamic content

After the formal announcement, the project quickly grew, with hundreds of biologists joining the effort. New features were added; one of my favorites were “treehouses”, which were collections of content written by or for children and a more general audience, and which focused on a particular group of life. Treehouses were attached to that group’s branches of the tree.

In February 2002, after a huge amount of work by three talented programmers, a version of the project debuted with a very different internal structure, with the content being produced dynamically by a database, rather than a series of static HTML pages. This change required all content to be moved back to the server in Arizona so that it could reside in a single database. In 2009 the server was moved to Oregon State University, where it has resided ever since. Alas, the software that runs ToLWeb is now so out of date that it causes a security risk, and so it needed to be disconnected from the Internet.

More details of the history of the project between 1996 and 2007 are provided in Maddison et al. (2007).

For the most part new content stopped being added to the project in 2011. There are multiple reasons for this, including a lack of resources to encourage and enable contributions, and to rewrite the underlying code so that it worked on more modern operating systems. Another significant factor was the rise of other projects such as the Encyclopedia of Life, which at the time captured the attention of many of our contributors. Perhaps most importantly I simply didn’t have the time to champion the project as it needed to have been to thrive. Contributions slowly petered out.

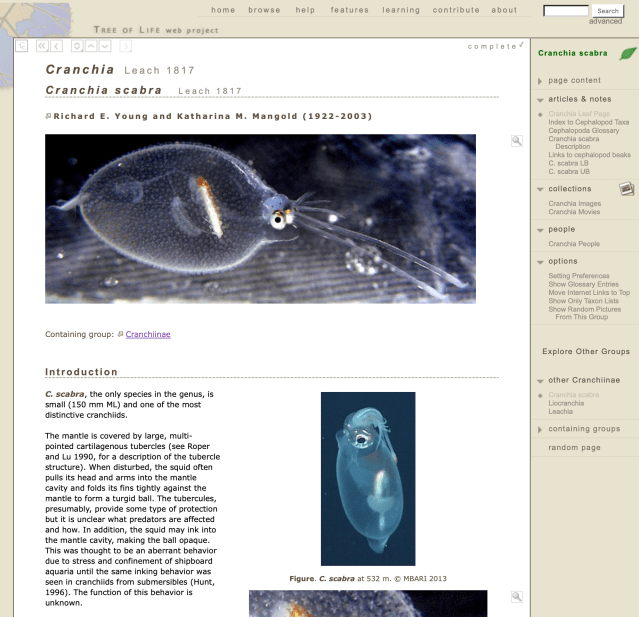

The last person to contribute content to the project was Dick Young, an expert in cephalopods, who put up many pages filled with the wonders of octopi, squids, and related animals. His enthusiasm over the years and the incredible diversity he showcased inspired me over the last decade to do what little I managed to do with the time I had available, and I wanted to keep it alive for him as much as anyone. And, really, how could you not fall in love the images and information Dick provided of a little creature like Cranchia scabra, shown below on one of Dick’s pages.

There were many other key contributors to the project. Most significantly there were the members of the “home team”: Wayne, especially in the early days; Travis Wheeler, Danny Mandel, and Andy Lenards, the three excellent programmers who created the underlying code of the database-driven version and made it all work; and especially Katja Schulz, without whose careful managerial and editorial work across many years the project would not have thrived.

In the end there were over 540 biologists from over 35 countries participating, contributing to the groups in which they were experts, and well over 10,000 pages of biological content.

At its peak (about 2006) ToLWeb was visited by over 2,500,000 unique visitors per year, from 198 countries and independent states. By 2023 the number of visitors per year dropped down to about 125,000, but even now I get emails from teachers telling me how important it is for their teaching.

The Future that was not to be

The endpoint of ToLWeb was so far from what our goals had been; it never reached our dreams. We had imagined a more flexible database that could allow alternative hypotheses about the branching pattern of the tree; the content atomized as content units with flexible criteria to map them onto nodes on the chosen tree; automatic inclusion of content from other databases, and numerous methods to map that content to particular nodes; synthesis of this content into tree decorated with content. We had imagined a vastly better interface, less page-oriented and more seamless, with the ability to wander through the tree more fluidly. We wanted a well-illustrated page for every species (for the Tree is not just branches, it is also “leaves”). There were other dreams, but they all faded under the reality of time.

The Future that may be

There are now several excellent projects that embrace some of the vision of ToLWeb.

The Open Tree of Life (https://opentreeoflife.org) is well-designed project into which the phylogenetic results from the primary literature are deposited, combined with existing taxonomic classifications, and algorithmically synthesized into a single, browsable tree of life. Although I suspect this way of producing the core tree structure will be the way of the future, and the group of people behind it are superb, its current state has a lot to be desired. There are two major problems: (1) the vast majority of phylogenetic knowledge has not yet been entered into their database, and for most species there are no phylogenetic hypotheses; (2) the algorithm used to synthesize the trees and classifications leads to some notably incorrect results. The lack of inclusion of phylogenetic hypotheses has many causes; it’s not an easy problem to solve. The problematic results of the synthesis algorithm are also likely not easy to solve.

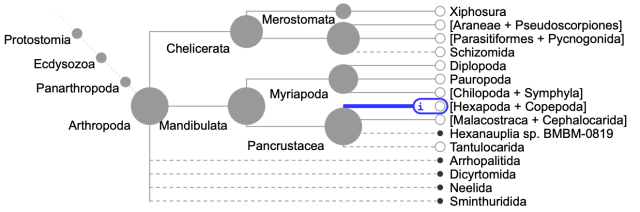

As one example of the tree presented in Open Tree, consider the root of arthropods in the tree. This is what that section of the tree looks like:

Note the taxon “Neelida”, toward the bottom. That is a group of springtails, which should not be shown in a basal polytomy with other major groups of arthropods, for it belongs fully within one of the other groups shown on at the tips of the tree – Hexapoda (highlighted in blue). Why Neelida, Sminthuridida, etc. are shown outside of Hexapoda I don’t know, but such issues are abundant at least in insects. In some groups (e.g., the ground beetles that I work on) these problems abound, with many species falling not within their groups but seemingly randomly attached to some much deeper node. The tree in those groups is pretty much nonsensical. Thus, using the tree provided by Open Tree in analyses within some groups can lead to inaccurate calculations; for the same reason the tree in portals such as One Zoom (which uses Open Tree as its primary source) should also be viewed with great caution. Again, this is not a fault of the vision of Open Tree, but rather its current status. Perhaps more funding of Open Tree will allow it to live up to its promise.

Other efforts, such as that presented by Del Risco et al. (2024) and embodied in their Tree of Life App for mobile devices, contain curated collections of phylogenetic hypotheses, synthesized into a singular view. Their app’s content is less automated than Open Tree, which means it requires more human effort to add components to the Tree, but has the advantaged that the components are more vetted. It is not currently organized as a collaborative project the way ToLWeb was organized, which had hierarchically organized communities of researchers working on ever smaller branches of the Tree.

The Encyclopedia of Life, https://eol.org, although containing a lot of great information, does not fundamentally embrace the phylogenetic vision and navigation that I think is vital.

I still believe there is an important place for a project like ToLWeb and its dreams: a phylogenetic view of all life, curated and synthesized by experts, allowing for alternative hypotheses, displayed and navigated fluidly in a single portal, onto which is layered text (including organismal characteristics), media (photographs, drawings, videos), and other data about the species and clades of the Tree.

A passing

And so the Tree of Life Web Project will transition to another phase. It likely will be offline for a while, as we work on a way to preserve its content for others to use. I should know in the next few months whether this is possible.

In the meantime, it should be available on the Wayback Machine, at https://web.archive.org/web/20251003172115/http://tolweb.org/tree/ Let’s hope it eventually has a life outside that archive.

But if not, I hope the project has served as an inspiration to others to create something even better in all ways.

References

Del Risco, A.A., Chacón, D.A., Ángel, L. and García, D.A. (2024), Assembling an illustrated family-level tree of life for exploration in mobile devices. J. Syst. Evol., 62: 993-1008. https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.13053

Maddison, D. R., K.-S. Schulz, and W. P. Maddison. 2007. The Tree of Life Web Project. Pages 19-40 in: Zhang, Z.-Q. & Shear, W.A., eds. Linnaeus Tercentenary: Progress in Invertebrate Taxonomy. Zootaxa 1668:1-766. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1668.1.4