Sigh.

I was painfully reminded yesterday of Maddison’s Law of Phylogenetic Analysis. It wasn’t the first time over the last few months I have been reminded of that law.

As I documented in my March 2023 blog post Prior and Current Ignorance: Struggles with Bayesian analyses, I have been attempting to do a Bayesian analysis of some beetle genomic data that would yield estimates of the divergence times of various branches in the evolutionary tree of Bembidion ground beetles. We (primarily James Pflug) had already completed numerous other analyses, including maximum likelihood analysis of various combinations of data, SVD Quartets, etc., etc. Only the Bayesian analysis remained.

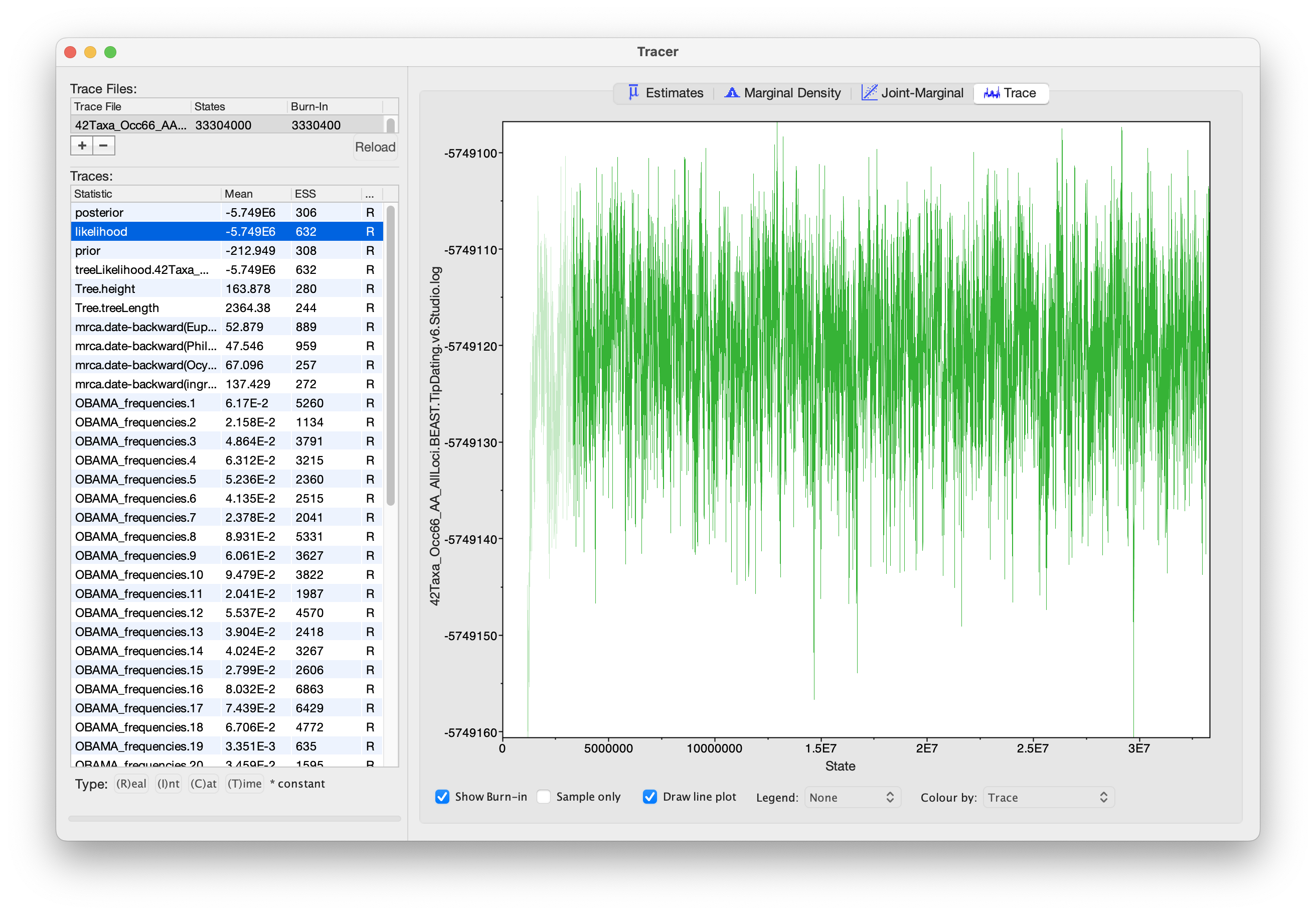

After I last updated that post, I started the final analysis in the program BEAST following the options outlined in the post. I set the BEAST 2.7 analysis going on 17 April 2023 on a relatively fast MacStudio (with an M1 Ultra chip with 16 fast cores and 128GB RAM). It happily did the whole MCMC sampling routine until about two months later, 16 June, when I stopped the analyses as the ESS values were all above 200. Here’s what the window in Tracer v1.7.2 looked like, showing on the right the trace for likelihood:

I was extremely pleased that this was done – my final analysis for the paper was done! But then I looked at the resulting trees and realized that the estimated age of Bembidiini was way too old at 175 million years, in the Jurassic. That is way older than makes sense based upon other dating analyses of beetles and the fossil record.

Searching online revealed the problem: the way the taxa were sampled violated the core assumption of randomness in the BEAST Fossilized Birth Death analysis. It turns out that if you sample taxa to maximize sampling of deep phylogenetic lineages, as I did, then using BEAST’s FBD random sampling model will cause overestimation of the ages (Matschiner et al. 2017). In the advice I received about the sampling model, which led to the exclusion of outgroups as they were sampled much less densely, there was no mention of this bias.

So where to go from here? There is a CladeAge package for BEAST (Matschiner et al. 2017) that is specifically built to avoid this bias in FBD analyses in BEAST. However, I didn’t get far with that, as CladeAge requires presumption of diversification rates (if I remember correctly), which might be fine for extremely well-studied groups like vertebrates with dense fossil records, but for my little beetles there simply isn’t the background knowledge to presume diversification rates that I felt comfortable with.

More exploration revealed that, thankfully, MrBayes could do the FBD analysis with the assumption that taxa were sampled across the deepest nodes, rather than randomly. This was great news, not only for me, but for the field, as most people who do phylogenetic studies make a point of sampling one or two species from each group; they do not randomly sample. So off into the MrBayes world I went.

The key commands for MrBayes were:

prset brlenspr=clock:fossilization;

prset samplestrat=diversity;

These told MrBayes to do an FBD analysis, and assume a sampling strategy that was meant to maximize diversity of deep lineages. Perfect! I did an initial test of how long it would take analyzing all 500,000 amino acids, and it seemed to be too slow, so I asked instead for it to analyze the data at the nucleotide level, but this time excluding 3rd positions (so about one million nucleotides). I also asked it to do 4 MCMC runs with 4 chains each. I began my final Bayesian analysis on 29 July 2023.

However…. things did not turn out as hoped. I just couldn’t get MrBayes to sample sufficiently. Two and a half months later, by 14 October 2023, it had completed nearly 22 million generations on the fast 16-core computer, but the ESS of ln L was only 6. Here’s what the Tracer view looks like of ln L:

As you can see, it looks pretty miserable. All four chains had eventually reached the same level for ln L but it seemed as if it would take an extraordinarily long time to sample sufficiently to complete the analysis. I also needed that computer for something else, so I decided to stop the run. That should be no problem, however, as MrBayes has a checkpointing system that allows a run to be restarted partway through.

Alas, I couldn’t get the checkpointing system to work. Tried multiple times, asked questions, got no where.

Because I suspected I could improve the sampling by altering the options for the MCMC process, I tried again with the MrBayes analysis, this time hoping that different values of the chain temperatures and swap frequency would be better. With hope in hand, I started my final Bayesian analysis on 16 November 2023. However, after 3.5 weeks of sampling, this is what the ln L trace looked like (on 11 December):

As it didn’t seem as if it was doing all that much better than the earlier run, and after much thought, and discussion with my colleague Katie Everson, I decided to abandon that run.

But it turns out I had another computer that was available during that time, and so I had already started to explore dating the branches not with the better method of the Fossilized Birth Death process, but instead a classic method in which nodes were calibrated with the fossils. So while that failed FBD analysis in MrBayes was going on, I was also running a calibrated node analysis in BEAST. This included all three fossil Bembidion, and the run was started on 23 October 2023. It finished, with good ESS values, on 6 December 2023. So when I decided to scratch the MrBayes run on 11 December, all was good, as I already had completed what was now my final Bayesian analysis five days before. Yay!

Except… as I was writing up the methods section, I realized that there was a problem with one of the fossils used to calibrate the minimum age of one clade. The placement of the fossil in that clade was less certain than I had originally thought. And so, with some reluctance, I decided to scrap that analysis, and start again, this time dropping that fossil and its calibration from the analysis. OK, whatever.

So now, at last, with some confidence I could begin my final Bayesian analysis: a calibrated node analysis in BEAST, with only two calibrated nodes (one of each of the two fossils) not three. I began the analysis on 6 December 2023, and one month later, on 6 January 2024, it had sampled enough that I felt comfortable stopping it and harvesting the trees. At least I was done!

Except… a couple of weeks later, while helping a colleague (Kip Will) with setting up an analysis for a joint project, I realized that we had mistakenly set one of the priors for the Optimized Relaxed Clock to something we shouldn’t have used. This meant that I had to start again.

I corrected that prior, and on 23 January 2024 I started my final Bayesian analysis, just like the previous one, but with the better prior. It chugged along for a few weeks, and on 12 February 2024, all ESS values were above 200, and so I stopped the analysis, breathed a huge sigh of relief that it was finally done.

Except… yesterday the author of the Optimized Relaxed Clock package in BEAST that we were using reported to the Google Groups community that there was a bug in the version of ORC that we used, and that it was strongly recommended that users redo any analyses.

And, so. Here we are again. Almost one year later. Yesterday night I started the run again. The seventh final Bayesian analysis. I figure it will be done in three weeks or so.

Will this truly be the final Bayesian analysis? Seventh time’s a charm? Who knows. Somehow I suspect not, unless I am just so sick of the whole thing that I abandon the analysis entirely. If, miraculously, I really complete the final analysis for this paper, I will update this post!

Now you can see why I was reminded yesterday of this law:

Maddison’s Law of Phylogenetic Analysis: You will conduct your final phylogenetic analysis at least three times.

References

Matschiner, M., Musilová, Z., Barth, J.I.M, Zuzana Starostová, Salzburger, W., Steel, M., Bouckaert, R., 2017. Bayesian Phylogenetic Estimation of Clade Ages Supports Trans-Atlantic Dispersal of Cichlid Fishes, Systematic Biology, 66:3–22, https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syw076

Pingback: Prior and Current Ignorance: Struggles with Bayesian analyses | The Subulate Palpomere

Hi David,

Thanks so much for your interesting posts. In addition to your amazing work on Bembidion, I greatly appreciate “the community of carabidologists” it creates, especially for the Pacific Northwest region, which is greatly needed.

You state in this post: “But then I looked at the resulting trees and realized that the estimated age of Bembidiini was way too old at 175 million years, in the Jurassic. That is way older than makes sense based upon other dating analyses of beetles and the fossil record.”

Just out of curiosity—-What are the other estimates for the ancient origination of the Bembidiini lineage, or closely related carabids? How far off are the estimates, and how do they compare to the hypothetical ranges based on statistical power of the different analyses.

James Bergdahl

Spokane, WA.